Guinea Pigs is a new play exploring the generational impact of moral injury in nuclear test veterans and their descendants.

“How much more mental harm has been done to the veterans and their descendants by the decades-long wait for an apology?” asks Elin Doyle, the play’s writer.

My partner, Damian, has just been diagnosed with PTSD following a serious head-on collision last September when a van crossed oncoming traffic without seeing him on his bicycle.

He was left with multiple head injuries, including a lower jaw in three parts after taking the brunt of the impact and probably saving his life, as well as two brain bleeds.

The brain is an incredible and mysterious thing. There’s so much that specialists understand about its functioning and yet there is still much that we don’t.

Damian’s physical recovery has mostly happened. The driver forgiven. The apparent impact of the brain injury has mostly settled with a few small exceptions.

Until a few weeks ago.

The driver, having pleaded not guilty to a charge of Driving Without Due Care And attention at their first court appearance will now be back in court to face trial and Damian has received a witness summons, though he has no memory of that day.

Cue the first ever anxiety attack of Damian’s life, launching a succession of inexplicable feelings of anger and angry outbursts, which have ultimately led to this diagnosis of PTSD. A diagnosis which hasn’t surprised me as I remember saying to his Occupational Therapist not long after he came out of hospital that he seemed almost “too okay” considering his near-death experience. The driver’s refusal to acknowledge their responsibility in the accident seems to have unleashed an inner, hidden trauma that has been lurking in the background since the accident.

Why am I telling you all this? (With his full permission, I might add).

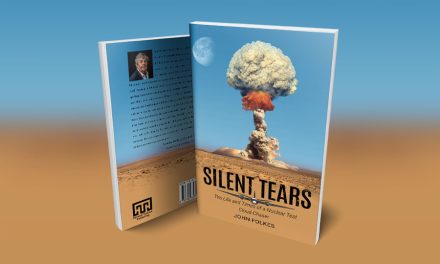

Well, this all comes two months before we open a play that I’ve been working on for the last few years. The play is about Gerry, a nuclear test veteran whose family has been blighted by his time at the Grapple X test and who, by the time we meet him, is clearly suffering trauma symptoms.

Set mostly in the 1980s, GUINEA PIGS is told through the eyes of Coral, Gerry’s idealistic teenage daughter (named after Christmas Island Coral). I wrote GUINEA PIGS from my own experience growing up in a nuclear test veteran family. Though to be clear, GUINEA PIGS is a fictional story about a fictional family that deliberately does not resemble mine.

I have a sibling with a birth defect and recently found out from Mum that my parents immediately put it down to the tests. I can only imagine the mixture of emotions Dad might have felt; anger, guilt, fear, betrayal? If he did, he can only have internalised these emotions because I was never aware of them being spoken about or expressed.

Dad experienced health issues himself that impacted on his ability to continue to be self-employed and he ended up in a series of menial jobs that must have been agony for someone who had successfully run their own business for 25 years. Add to this the financial difficulties my parents experienced as a result and Dad was still working until the day he died. For many years during my childhood, Dad’s spare time was sucked up by his time as an active member of the BNTVA during the early years of the test veteran campaign.

And yet we never joined up the dots. We never understood why Dad, who was on the one hand an incredibly kind, generous, funny and intelligent man but on the other hand could start a row with his own shadow as soon as we were outside the home. God help the waitress slow to serve our table or the person who accidentally queue-hopped in front of us. The one thing he couldn’t bear was injustice and saw red wherever he perceived it, seemingly unable to determine a great injustice from a minor annoyance. I was the only child in school who on Parents’ Evening was even more worried about what Dad would say to my teachers than what they had to say to him! (And they had some stuff to tell him, believe me.)

Things got to the point where we dreaded going anywhere with him because it happened everywhere. We never realised. We didn’t have the vocabulary back then.

And even if we did, it just wasn’t something that men who were teenagers in the 1950s talked about. Not wanting to put too much of an armchair psychologist’s romanticised spin on it – but was he subconsciously trying to protect us in a way that he hadn’t been able to protect us before, when the people he’d trusted to keep him and his descendants safe had broken that trust?

To avoid confusion, PTSD is not the same as moral injury, though they do share some similar traits; anger, depression or addiction. Whereas PTSD occurs following threat-based trauma, such as threat to life in active service or civilian life, an assault or a serious accident, moral injury is caused by events that threaten a person’s deeply held beliefs and trust.

A Lancet article from March 2021 describes moral injury as;

“…the strong cognitive and emotional response that can occur following events that violate a person’s moral or ethical code. Potentially morally injurious events include a person’s own or other people’s acts of omission or commission, or betrayal by a trusted person in a high-stakes situation…”

Nuclear test veterans can suffer from both PTSD and moral injury.

However, as portrayed in GUINEA PIGS and as I am again reminded by Damian’s recent experiences; when one family member is going through something, the whole family goes through it with them, which is why I describe the play as “exploring the generational impact of moral injury.”

When I wrote GUINEA PIGS, I hadn’t even heard the term moral injury and I never set out to write about it. What I did set out to write was the test veteran story from my own truth. From how I experienced it as the young daughter of a nuclear test veteran. It wasn’t until I spoke with Ceri McDade, CEO of the BNTVA, I discovered what I’d written about was moral injury. I’m glad it worked out that way because in not knowing anything about moral injury beforehand, there’s nothing contrived or set-up in its depiction.

This year, both the BNTVA and the NCCF have been very supportive of the play, an acknowledgement for which I’m hugely grateful. I hadn’t really considered myself part of the nuclear community because I’ve never been particularly involved – probably because Dad was so active in my childhood and after he died, we just wanted to move on. But I’ve come to realise that whether actively involved or not, I am a member of the nuclear community by definition of the fact I am the daughter of a test vet.

It’s been great to see the renewed media interest with the BNTVA once more engaging with a broader media. I found myself in tears watching Ceri’s recent interviews with Naga Munchetty on the BBC Breakfast sofa. Tears that surprised me by springing from nowhere, triggered by something deeply internal, which I realised was Naga and her co-host’s obvious shock and curiosity at learning about the test veterans’ story – how many decades have I watched broadcast journalists express the same shock and curiosity at the test veteran story? How come people still don’t know?

Why are we still here all these years later? Why is the story still not publicly known and a proper apology and resolution found? How many of our nuclear test veterans have died in the intervening years between the 1980s when I watched the likes of my dad, Ken McGinley and others interviewed on TV sofas, to the TV sofas Ceri was interviewed on this year?

For me, that is where the moral injury also lies; not only in the acts of commission of sending young men into a live testing environment and the acts of omission in failing to protect them and provide proper medical aftercare – but also in the intervening years that successive governments have refused to acknowledge their responsibility in the aftermath of the tests and their duty to care for those involved. Rather like the driver of the car that took a right turn across oncoming traffic and failed to see a cyclist on a straight piece of cycle lane in front of them.

It’s for the test vets we lost before they could hear an apology that my anger is fuelled.

Despite its hard-hitting topic, GUINEA PIGS is essentially a heart-warming story with much light relief found in Gerry and Coral’s relationship. Coral’s teenage idealism makes for some great comedy moments, especially for those with a nostalgia for the ‘80s.

Actor, Jonny Emmett, who plays Gerry is himself a service veteran. As a former paratrooper turned actor, Jonny lives with a diagnosis of PTSD stemming from his service during the Northern Ireland troubles. He is active with both veteran charities Combat Stress and Odin’s Oath, a charity for homeless veterans. Caron Kehoe, who plays Coral’s Aunty Maureen (Gerry’s Sister) is a writer, director and performer. She is a co-founder of Yellow Coat Theatre Company – a cross-generational, female-led collective. Originally from Liverpool, Caron is now based in SE London and continues to create work that focuses on celebrating women’s experiences through innovative and energetic theatre. Our director, Sam Chittenden, Artistic Director of A Different Theatre also spent some time at Greenham Common during her student years. And me, actor, writer and producer? Well, I was the young idealistic teenage daughter of a nuclear test vet in the 1980s…

Rehearsals begin in September for a short run at The Space, London. Performance dates are timed to coincide with the 70th anniversary of Operation Hurricane, which saw Britain’s first live nuclear test on 3rd October 1952. Our aim is to use this short run as a platform to launch us into our next phase; touring the play around the UK in 2023.

We are incredibly grateful to the NCCF who are offering to cover the ticket cost of any London-based nuclear test veterans or descendants wishing to attend these London performances.

We have already been contacted by a number of nuclear descendants whose response to the play has so far been overwhelmingly positive, especially in knowing their story will be shared to a wider theatre audience. This is what I want, in particular – for the community to feel seen and for the wider public to know our story.

However, due to some of the storyline, there may be elements that are triggering for some and so we highly recommend that audience members exercise caution when booking, with subjects touched upon such as family separation, infant mortality and graphic description of a live nuclear test.

GUINEA PIGS will run at:

The Space

269 Westferry Road

London

E14 3RS

from 4th – 8th October 2022.

The performance of Friday 7th October will be live-streamed and also include a post-show Q&A.

Photography and poster image by Damian McFadden – www.damianmcfadden.com

Free Tickets are available for the show, for more information click here.